What is a Descriptive Essay?

A descriptive essay is a type of writing that uses sensory details and vivid language to create a clear picture of a person, place, object, event, or experience in the reader's mind. The main goal isn't to argue a point or tell a story with a plot; it's to describe something in such rich detail that your reader can almost see, hear, smell, taste, or touch what you're writing about.

Key characteristics that define descriptive essays

- Heavy reliance on sensory details (sight, sound, smell, taste, touch)

- Vivid, specific language rather than abstract descriptions

- Clear dominant impression or central theme

- Organized structure (spatial, chronological, or by importance)

- "Show, don't tell" approach throughout

When You'll Write Descriptive Essays

Students typically encounter descriptive essay assignments in:

- English composition courses

- Creative writing classes

- College application essays

- Standardized tests (SAT, ACT writing sections)

- Literature and analysis courses

Teachers assign them because descriptive writing develops crucial skills: precise word choice, attention to detail, and the ability to create immersive experiences through language alone.

How Descriptive Essays Differ from Other Essay Types

Unlike narrative essays that focus on storytelling with a clear beginning, middle, and end, descriptive essays zero in on a single moment or subject. And unlike expository essays that explain or inform through facts and analysis, descriptive essays aim to create an immersive sensory experience.

Why Descriptive Essays Matter

Descriptive writing skills extend far beyond academic assignments. Strong descriptive writing appears in:

- Travel journalism and blog posts

- Product descriptions in marketing

- Creative fiction and memoir

- Scientific observation reports

- Technical documentation

- Grant proposals and case studies

Mastering descriptive techniques makes all your writing more engaging and memorable. It's a foundational skill that elevates every other form of writing you'll encounter.

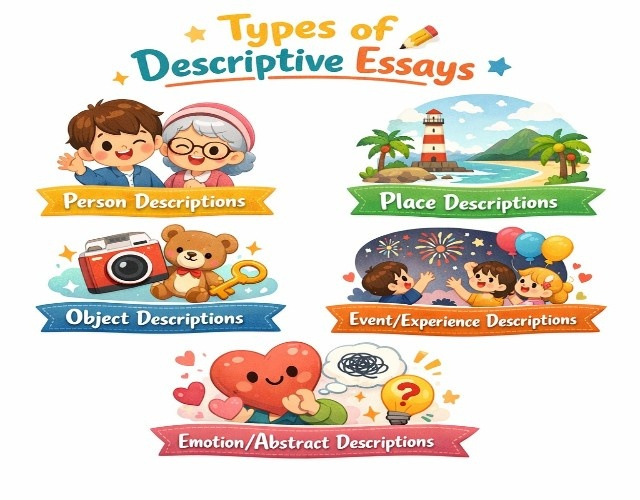

Types of Descriptive Essays

Understanding the different types of descriptive essays can help you choose the right approach for your assignment. Here are the five main types you'll encounter:

1. Person Descriptions

These essays focus on describing someone's physical appearance, personality traits, mannerisms, and characteristics. You might write a descriptive essay about your mother, a teacher who influenced you, a historical figure, or a descriptive essay about someone you admire. The key is capturing both how they look and who they are as a person.

For detailed guidance on this type, check out our descriptive essay about a person guide, which includes examples and specific techniques for bringing people to life on the page.

2. Place Descriptions

Place descriptions focus on locations, settings, and environments, whether real or imagined. You might describe your favorite beach, your hometown, a memorable vacation spot, or even a fictional setting. These essays often use spatial organization to help readers visualize the location.

Our descriptive essay about a place resource offers specific strategies for describing locations effectively, from small rooms to vast landscapes.

3. Object Descriptions

Object descriptions center on items, possessions, or meaningful things. This could be a family heirloom passed down through generations, your favorite book with its dog eared pages, or a childhood toy that holds special memories.

The challenge here is making an ordinary object come alive through the memories and details you associate with it.

4. Event/Experience Descriptions

These essays describe moments, experiences, or occasions: your first day of school, an unforgettable concert, a holiday celebration, or a life changing trip.

While they might seem similar to narrative essays, the focus is on describing what the experience was like rather than telling a story with conflict and resolution.

5. Emotion/Abstract Descriptions

The most challenging type, these essays describe feelings, concepts, or intangible ideas like fear, happiness, love, or freedom.

Since you can't physically see or touch emotions, you'll need to use metaphors, concrete examples, and sensory details to make abstract concepts tangible for your reader.

Remember! Studying descriptive essay examples helps students learn how to use vivid sensory details, strong imagery, and precise language to create engaging and immersive descriptions in their own writing.

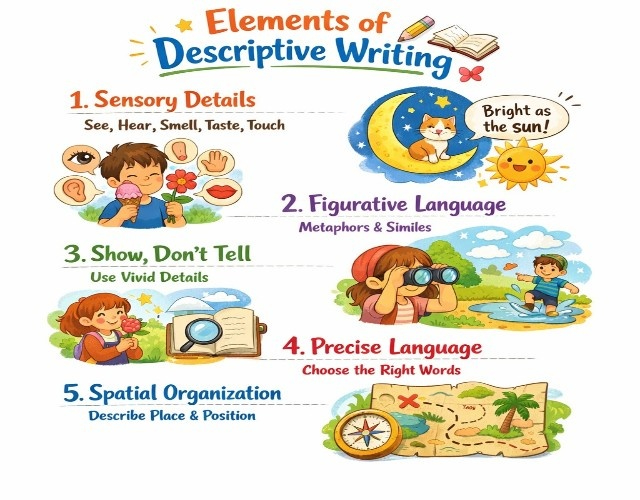

Elements of Descriptive Writing

To write an effective descriptive essay, you need to master several key elements that work together to create vivid, engaging prose. Let's break down what makes descriptive writing powerful.

1. Sensory Details

The foundation of descriptive writing is engaging all five senses: sight, sound, smell, taste, and touch. This transforms flat writing into something immersive.

General rule: Include at least three different senses in each paragraph. This multi-sensory approach creates complete immersion.

2. Figurative Language

Figurative language helps readers understand your descriptions by comparing unfamiliar things to familiar ones. The three main types you'll use are similes, metaphors, and personification.

Similes use "like" or "as" to make comparisons:

Metaphors state that something IS something else:

Personification gives human qualities to non human things:

|

When used sparingly and appropriately, figurative language adds depth and creativity to your descriptions. Just don't overdo it, one strong metaphor is better than five mediocre ones.

3. Show, Don't Tell

This is perhaps the most important principle in descriptive writing. "Telling" means stating facts about emotions or characteristics directly. "Showing" means revealing those same things through specific details, actions, and sensory information.

Telling: "She was nervous." Showing: "Her hands trembled as she gripped the podium, and her voice cracked on the first word." |

Telling: "The house was abandoned." Showing: "Ivy snaked through the broken windows, and the porch sagged under layers of rotting leaves." |

Try this practice exercise: Take three "telling" sentences you might naturally write, then convert each one to "showing" by describing what someone would see, hear, or feel instead of naming the emotion or state directly. For a complete guide on character descriptions, see our article on descriptive essay about a person.

4. Precise Language

Vague, generic words are the enemy of good descriptive writing. Instead of saying someone "walked," choose a specific verb that shows exactly how they moved:

|

Instead of saying something was "big," use an adjective that conveys the specific type of bigness:

?Avoid weak, overused words like "nice," "good," "bad," "thing," "very," and "really." These words don't create pictures in your reader's mind. Every time you find yourself using one of these words, stop and ask yourself: "What do I really mean?" Then find the precise word that captures that meaning.

5. Spatial Organization

Especially when describing places or physical appearances, spatial organization helps your reader visualize what you're describing. This means describing things in a logical order based on physical space:

- Top to bottom: Start with someone's hair and work down to their shoes

- Left to right: Describe a room from one side to the other

- Near to far: Begin with what's closest and move to what's in the distance

- Outside to inside: Describe a building's exterior before taking readers inside

For Instance, when describing a room, you might start at the doorway and move clockwise around the space. This gives readers a mental map and prevents confusion about where everything is located.

How to Write a Descriptive Essay (6 Step Process)

Now that you understand the elements of descriptive writing, let's walk through the actual process of writing your essay from start to finish.

Step 1: Choose Your Focus

The first step is selecting something worth describing. The best topics are subjects that are meaningful to you, familiar enough that you can recall specific details, or interesting enough that you're motivated to observe carefully.

Your topic should have rich sensory details available to describe. A blank white wall might be hard to write about, but your grandmother's cluttered kitchen with its copper pots, herb garden on the windowsill, and worn wooden table covered in flour dust gives you plenty to work with.

If you're stuck choosing a topic, our Descriptive Essay Topics guide offers 250+ ideas organized by category, from people and places to objects and experiences. Sometimes seeing a list of possibilities is all you need to spark inspiration.

Step 2: Gather Sensory Details

Before you start writing, spend 5 to 10 minutes brainstorming sensory details about your topic. Create a five column chart with headers for each sense: sight, sound, smell, taste, and touch.

If you're describing something from memory, close your eyes and try to recall specific details. If you're describing something you can currently observe, take notes as you look around and really pay attention.

Here’s a chart describing “Beach at Sunset”:

Sight | Sound | Smell | Taste | Touch |

Orange and pink sky | Crashing waves | Salt air | Salty spray on lips | Warm sand |

Silhouettes of seagulls | Children laughing | Sunscreen | Sweet ice cream | Cool ocean breeze |

Foam on waves | Distant music | Seaweed | Ocean Salt | Rough driftwood |

Footprints in sand | Seagulls crying | Coconut lotion | Tangy Seaweed | Wet swimsuit |

You won't use every detail you brainstorm, but having this list gives you options when you're writing. It also ensures you're not relying too heavily on just one or two senses.

Step 3: Create a Framework

Don’t skip this step. Proper planning keeps your essay organized and prevents rambling or repetition.

For most descriptive essays, the standard five paragraph structure works well: You can also organize by spatial order if you're describing a physical space, or by order of importance if you're describing something complex (most significant details first, less important details later).

Our descriptive essay outline guide provides detailed templates for different organizational patterns, so you can choose the structure that best fits your topic.

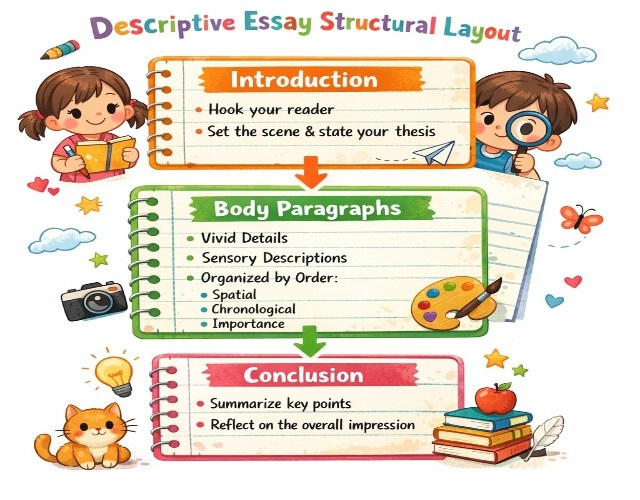

Step 4: Write Your Introduction

Your introduction needs to accomplish three things: hook the reader, provide context, and present your thesis statement.

Start with a compelling hook; we'll cover different hook types in detail in a later section. After your hook, provide necessary context: what or who you're describing, where and when this takes place, and why this subject matters.

Your thesis statement in a descriptive essay is different from other essay types. Instead of making an argument, your thesis conveys the main impression you want readers to have. It should capture the dominant feeling or most important characteristic of your subject.

This thesis doesn't argue anything, but it tells readers exactly what impression they should walk away with: warmth, comfort, sanctuary. Every detail in your essay should support this central impression.

Step 5: Develop Body Paragraphs

Each body paragraph should focus on one main idea or aspect of your subject.

Organize each paragraph

- Start with a clear topic sentence

- Include 3 to 5 supporting sentences packed with sensory details and figurative language

- Use transitions to connect ideas and help readers follow your description

- Maintain consistent point of view throughout

Keep paragrapa hs relatively short, 4 to 6 sentences is ideal. Long, dense paragraphs are exhausting to read, especially in descriptive writing where you're asking readers to visualize complex details.

Pro Tip: End each body paragraph with a sentence that either transitions to the next topic or reinforces your main impression. This keeps your essay cohesive rather than feeling like a random list of observations.

Step 6: Write the Conclusion

Your conclusion should restate your main impression without simply repeating your thesis word for word. Leave your reader with a lasting image or final sensory detail that captures the essence of what you've described.

Reflect on the significance or meaning of your subject. Why does this person, place, or thing matter? What should readers take away from your description?

Don't introduce new details in your conclusion. By this point, you should have painted a complete picture. The conclusion is about stepping back and letting readers appreciate the full image.

Get Your Descriptive Essay Today

Professional writers deliver quality essays in as fast as 6 hours.

Join 50,000+ students who trust MyPerfectWords

Descriptive Essay Structural Layout

Understanding proper formatting ensures your essay looks professional and meets academic standards. Let's cover the structural and formatting requirements you'll need to follow.

Standard Format

Descriptive essays typically follow a five paragraph format to ensure logical organization.

For longer or more complex topics, you can extend this to an introduction, 4 to 6 body paragraphs, and a conclusion. The key is that each body paragraph should cover one distinct aspect of your subject. |

Standard formatting requirements include

|

Always check your assignment guidelines, as some instructors have specific formatting preferences that differ from these standards.

Organization Patterns

How you organize your descriptive essay depends on what you're describing. Here are the three most common patterns:

1. Spatial Order (Best for physical descriptions)

Use this when describing places, objects, or people's appearances. Move through space in a logical way:

- Top to bottom

- Left to right

- Near to far

- Outside to inside

Example: When describing a room, you might start at the doorway, describe what's straight ahead, then move clockwise around the space before finishing with the view out the window.

2. Chronological Order (Best for experiences/events)

Use this when describing something that unfolds over time:

- Beginning to end

- Morning to evening

- Before to after

Example: Describing a day at the beach might start with arriving in the morning (cool air, empty sand), move through the afternoon (crowds, heat, swimming), and end with sunset (changing colors, quieter atmosphere).

3. Order of Importance (Best for complex subjects)

Use this when describing something with multiple aspects, starting with the most significant or noticeable features:

- Most to least important

- Most to least obvious

- General to specific

Example: Describing a person might start with their most striking characteristic (perhaps their laugh or their intense eyes), then move to their appearance, and finally to subtler personality traits.

For specific templates and visual diagrams of these organizational patterns, check out our Descriptive Essay Outline guide, which includes downloadable templates you can customize for your topic.

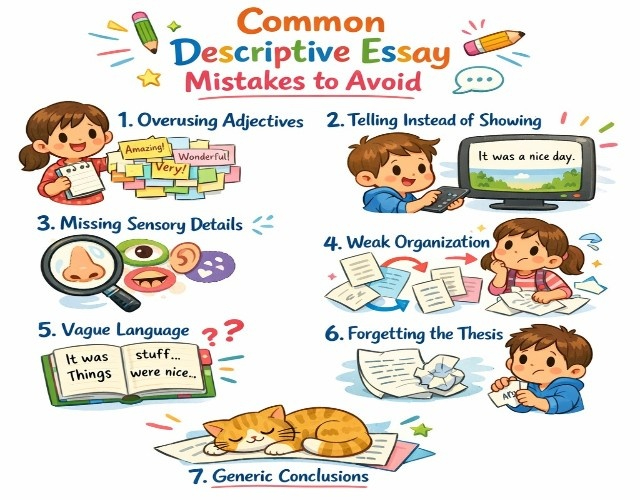

Common Descriptive Essay Mistakes to Avoid

Even experienced writers make these mistakes in descriptive essays. Learning to recognize and avoid them will immediately improve your writing quality.

1. Overusing Adjectives

Problem: "The beautiful, magnificent, gorgeous, stunning sunset was incredibly amazing." When you pile on adjectives, they lose their power. Your reader stops visualizing and starts skimming. Fix: Choose ONE strong adjective and pair it with sensory details that show why something deserves that description. Better: "The sunset blazed orange and pink across the horizon, setting the clouds on fire." This version uses just one adjective ("blazed") as a verb, then shows us the colors and creates a visual metaphor. That's much more powerful than five generic adjectives. |

2. Telling Instead of Showing

Problem: "The abandoned house was scary." Saying something is scary doesn't make your reader feel scared. You need to show them what makes it scary through specific details. Fix: Describe observable details that create the feeling you want readers to have. Better: "The abandoned house sagged under the weight of ivy, its broken windows staring like hollow eyes, and something inside creaked with each gust of wind." Now readers can picture exactly why this house is unsettling. You've shown scariness without naming it. |

3. Missing Sensory Details

Problem: Relying only on visual descriptions while ignoring the other four senses. Most beginning writers describe only what something looks like. But real experiences involve all five senses, and so should your descriptive writing. Fix: Aim for at least three different senses per paragraph. Challenge yourself to include smell, sound, taste, or touch, not just sight. If you're describing a bakery and you haven't mentioned the smell of bread or the warmth from the ovens, you're missing opportunities to make your description more immersive. |

4. Weak Organization

Problem: Jumping randomly from one detail to another with no logical flow. When details appear in random order, readers get confused about where things are located or how they relate to each other. It's like trying to assemble furniture without instructions. Fix: Choose an organizational pattern (spatial, chronological, or order of importance) and stick with it consistently. Use transition words to guide readers through your description: "Meanwhile," "Nearby," "In the corner," "Above the mantel," "As evening approached." These phrases create a roadmap that prevents confusion. |

5. Vague Language

Problem: "The food was good." / "She walked away." These sentences don't create any mental image. "Good" could mean a thousand different things, and "walked" tells us nothing about how she moved. Fix: Be specific. Find the precise word that captures exactly what you mean. Better: "The pasta melted on my tongue, rich with garlic and butter." / "She stormed away, heels clicking angrily against the tile." Now we know exactly what kind of "good" the food was, and we can picture exactly how she left. Precision creates clarity. |

6. Forgetting the Thesis

Problem: Describing everything about your subject without focus, creating a random list of observations. Just because something is true about your subject doesn't mean it belongs in your essay. Every detail should support the main impression you stated in your thesis. Fix: Before including any detail, ask yourself: "Does this support my thesis?" If the answer is no, cut it, no matter how interesting or well written it might be. If your thesis says your grandmother's kitchen is "warm and comforting," don't spend a paragraph describing the broken appliances or the stain on the ceiling. Those details contradict your main impression. |

7. Generic Conclusions

Problem: "In conclusion, the beach is beautiful." This adds nothing. Readers already know the beach is beautiful; you've spent five paragraphs describing it. Simply restating your thesis word for word wastes your conclusion. Fix: End with a reflection or a lasting image that gives meaning to your description. Better: "Even now, years later, I can close my eyes and feel the warm sand between my toes, hear the rhythm of the waves, and remember why that beach will always feel like home." This conclusion doesn't just repeat what was said; it reflects on the significance and leaves readers with a final sensory image that reinforces the emotional connection. |

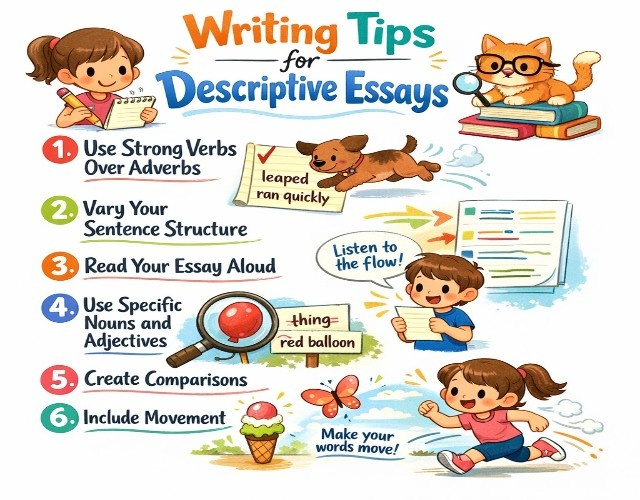

Writing Tips for Descriptive Essays

Here are additional strategies to elevate your descriptive writing from good to exceptional.

1. Use Strong Verbs Over Adverbs

Instead of modifying weak verbs with adverbs, choose powerful verbs that carry their own energy.

|

Strong verbs make your writing more dynamic and eliminate unnecessary words.

2. Vary Your Sentence Structure

Mix short, punchy sentences with longer, flowing ones. This creates rhythm and prevents monotony.

"The room was silent. Not the comfortable silence of an empty home, but the heavy, oppressive silence of secrets kept, and words left unsaid. I stood in the doorway, afraid to disturb the stillness."

Notice how the short first sentence creates impact, the longer second sentence builds tension, and the medium length third sentence provides resolution.

3. Read Your Essay Aloud

This is the single most effective editing technique for descriptive writing. When you read aloud, you'll immediately catch:

|

If you stumble while reading, your reader will stumble too. Rewrite until the essay flows smoothly when spoken.

4. Use Specific Nouns and Adjectives

Generic words create generic images. Specific words create vivid pictures.

|

The more specific you are, the clearer the image in your reader's mind.

5. Create Comparisons

When describing something unfamiliar, compare it to something your reader knows.

"The fruit tasted like a cross between a mango and a peach, with the texture of a ripe pear."

This gives readers a reference point, even if they've never tasted this particular fruit.

6. Include Movement

Static descriptions can feel lifeless. Add movement to create energy:

|

Movement makes scenes feel alive and dynamic rather than frozen in time.

Pro Tip: Keep a "sensory word bank" in your notes. Whenever you encounter a particularly vivid or precise word in your reading, add it to your bank. Categories might include: texture words, sound words, smell words, movement verbs, etc. When you're writing and struggling to find the right word, consult your bank for inspiration.

Conclusion

Writing a descriptive essay doesn't have to be intimidating. When you break it down into manageable steps, choosing a meaningful topic, gathering sensory details, creating an outline, and focusing on showing rather than telling, the process becomes much more approachable.

Remember these key principles: engage all five senses, use specific and precise language, organize your details logically, and make every description support your central impression. Avoid common pitfalls like overusing adjectives, telling instead of showing, and relying only on visual descriptions.

Now you have everything you need to write a descriptive essay that brings your subject to life on the page. Pick your topic, gather your sensory details, and start writing. Your reader is waiting to see, hear, smell, taste, and touch the world you're about to create.

Struggling with multiple deadlines? Get expert support from our professional essay writing service and stay on track with confidence.

Bring Your Descriptive Essay to Life Get expert help turning ideas into vivid, engaging writing Join 50,000+ students who trust MyPerfectWords.

-20161.jpg)

-20188.jpg)

-20358.jpg)

-20173.jpg)